Henry Ford had numerous unusual ideas that distinguished him from professionally trained businessmen and engineers. At the end of World War I, he developed the idea for Village Industries. His huge Highland Park plant produced thousands of Model T’s every day; indeed, production was so great and increasing so rapidly that he began to shift vehicle production to the River Rouge plant that he constructed several years earlier when the federal government asked him to build boats for the Navy. Those huge plants eventually hired tens of thousands ofmen. Ford needed many small parts every day for his busy production lines. He decided to manufacture some component parts in small plants in villages and towns near Detroit. Apparently, he had several reasons for doing this, but there is still debate about those reasons.

The Village Industries were located in rural areas and small towns and employed modest numbers of workers. They worked in a setting similar to Nineteenth Century manufacturing rather than the massive production line strategy that Ford perfected. Henry Ford never wrote a long

explanation for his two-decade-long experiment with Village Industries. Since he made all the key decisions for his company, he did not have to present a detailed management plan to a Board of Directors nor did he have to get the approval of bankers or investors. At this time, there were few local, state or federal regulatory agencies that might have requested long technical documents about the environment impact of turning an old mill into a parts factory. Those who have written about Henry Ford and his Village Industries speculate that Ford knew that farmers’ incomes were low and that many of them could work in a nearby plant and still maintain their fields and herds. Most likely, this was Ford’s motivation. Ford also had a consistent interest in what we now call alternative sources of energy. By the end of World War I, he thought that the world would someday run out of petroleum and have to turn to other sources. He used coal extensively to power his major production plants. Indeed, he owned coal mines in Kentucky and purchased the Detroit Toledo and Ironton Railroad to transport that coal to Dearborn. He knew the high cost of mining and transporting coal and the challenges of burning it efficiently. Thus, many or most of his Village Industry plants were former water-powered mills located on rivers. In several of them, Ford insisted that long-idle water power system be restarted. Ford believed that the United States would not or, perhaps should not, become a nation of huge cities such as Detroit. He expected the growth of many moderate-sized cities, so his anti-urban views may have encouraged him to experiment with Village Industries. By the time he started his Village Industries—1920—the huge Studebaker factory on Piquette in Detroit adjoining his own Piquette Street plant where he designed the Model T, had been unionized. Ford stridently opposed unions and this may have played a role in his decision to create small plants in rural areas, but I have never seen any documentation of this. Ford employed numerous black workers in his Dearborn and Highland Park plants, but apparently only one Village Industry—Ypsilanti—hired black workmen.

Henry Ford established 19 village industries in southeast Michigan: the first one—in Northville—opened in 1920, while the last one—in Cherry Hill—started production in 1945. Only two of the 19 small factories closed before the end of World War II, but 16 more of them were shuttered between 1947 and the late 1950s. The management at Ford that followed Henry Ford found the Village Industries inefficient and did not share his motivations. The one in Northville remained in operation until 1989. The employment in the factories ranged from a low of just 19 workers in the Saline and Sharon Mills plants to about 1,500 in the Ypsilanti plant.

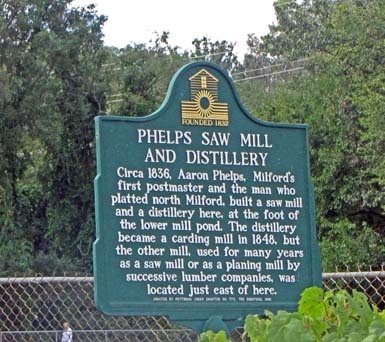

The village of Milford was founded in 1832. Shortly thereafter, mills were established along the Huron River and Pettibone Creek. In 1871, a north-south rail line reached the village that soon linked Milford to Detroit, Toledo and Flint. Local products could easily be shipped to regional markets. Milford became a manufacturing center as five dams were built to capture the power of the flowing water. There were sawmills, a grist mill, a cider mill, a foundry, a hydroelectric plant and a distillery. As the vehicle industry boomed, at least one parts manufacturer, Detroit Auto Dash, built a plant in Milford.

Milford, similar to almost all areas of Michigan, suffered greatly from the loss of jobs in the Great Depression. A local entrepreneur, Frank Hubbell, knew Henry Ford and encouraged him to set up a Village Industry so that men in Milford could find employment. Ford capitalized upon that idea and included Milford as a Village Industry. I am not sure about the history of the buildings. Pictures of this Village Industry show rather large plants, not just a Nineteenth Century mill. Perhaps the factory that Ford used for this Village Industry had previously been the home of Detroit Auto Dash. It is also possible that Ford had Albert Kahn design at this location. In any event, for quite a few years after 1938, almost all carburetors for Ford vehicles were made in the plant here in Milford. Apparently, there was much joy in Milford in 1938 when many of the boys graduating from high school immediately found employment with Henry Ford. At its peak in 1939, this plant employed 438. Henry Ford very strongly opposed unions and believed they had no right to organize his workers, despite the Wagner Act that demanded that employers recognize legally certified unions. Ford kept unions out of his plants until World War II forced him to recognize the UAW. Milford is one of the few Village Industries that was unionized.

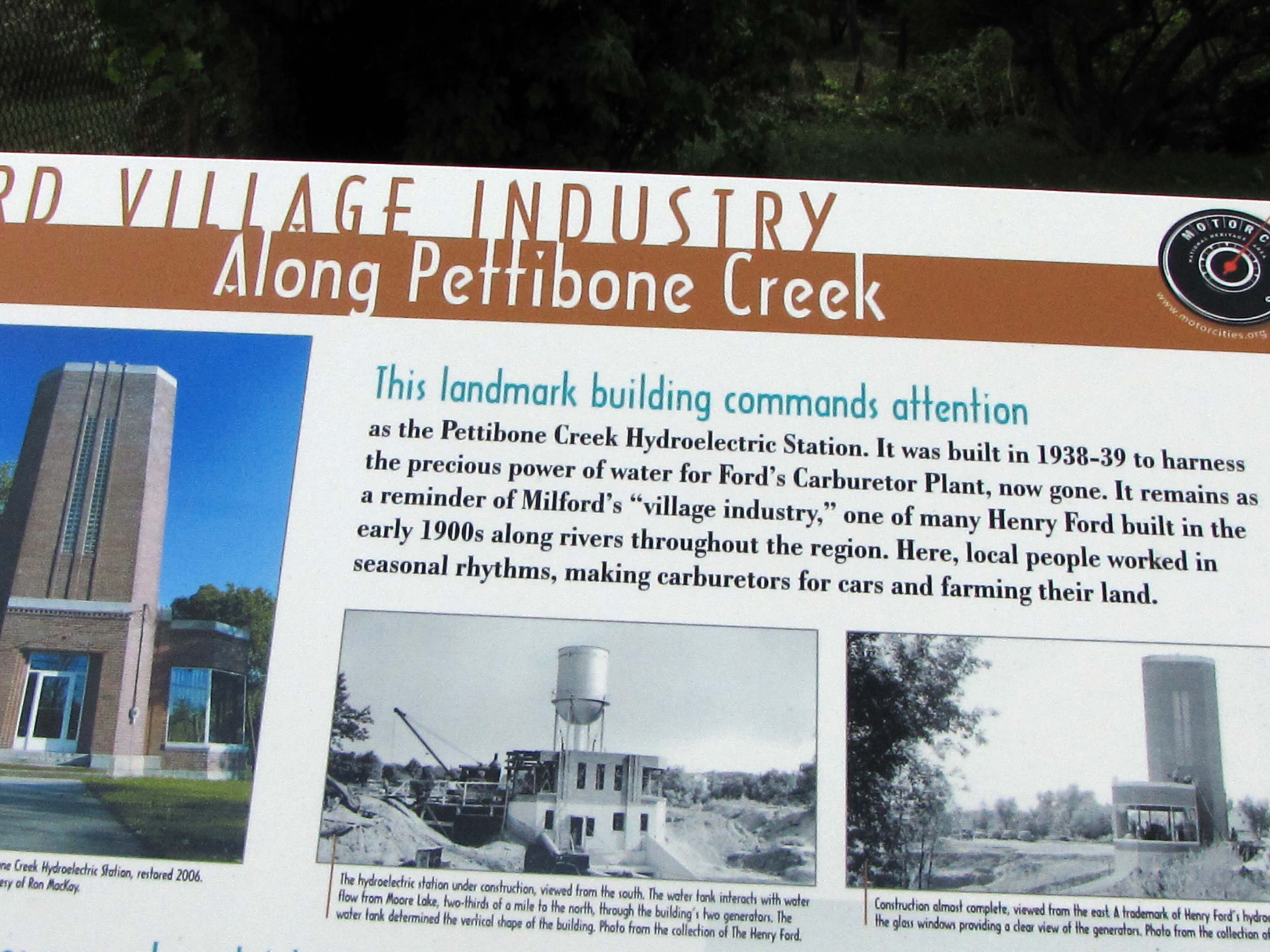

The Art Deco building you see pictured above is the hydroelectric station that Ford built in 1939, designed by Mr. Ford’s favorite architect, Albert Kahn. This Village Industry survived for quite a few years after World War II, but by 1958, the work was transferred to the much larger and more modern plant in Rawsonville. The parts manufacturer, Kelsey-Hayes, used the Milford Ford factories into the 1980s. However, gentrification occurred as this village capitalized upon its fine stock of housing and moved away from its original industrial roots to become an upscale and sylvan Oakland County suburb. The unattractive Ford plants were torn down and some of the campus converted into a park near downtown. The local historical society is now seeking funds to maintain the distinctive quality of the Hydroelectric Station pictured above. That historical society has placed quite a variety of attractive, informative plaques around Milford telling present-day residents of the manufacturing that was once accomplished in their city. The plaque on this page reminds visitors that whiskey was distilled on this property long before Henry Ford made his carburetors here.

Date of Construction of Remaining facility: 1939

Architectural Style: Art Deco

Architect: Albert Kahn

Use in 2010: This is an adornment in a large public park but is enclosed by stout wire fencing. The Milford Historical Society has plans for renovating this facility and, I presume, opening it to the public.

Website for Milford Historic Society Henry Ford Powerhouse Restoration Project

http://www.milfordhistory.org/power_station_project_page.html

Website for Map of Henry Ford’s Village Industries: http://www.milfordhistory.org/PDF/FordMap.pdf

Book about Henry Ford’s Village Industries: Henry Ford’s Village Industries: Recasting the Machine Age by Howard P. Segal (Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 2005)

State of Michigan Registry of Historic Sites: Not listed

National Register of Historic Places: Not listed

Picture: Ren Farley; September 4, 2010

Return to Ford Village Industries

Return to Home Page