The Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railroad was organized in Cleveland in 1869 in the hopes of capitalizing upon the shipment of goods and people from the Midwest to the East Coast. Railroad entrepreneurs had, for several decades, sought to develop a fast, relatively level route from the East Coast to Chicago which was the gateway for the Midwest. English investors funded the building of the Grand Trunk Railroad that stretched from the port of Portland, Maine into Quebec and Montreal and then on to Toronto, then to Sarnia and then to Detroit where a connection was made with the Michigan Central’s route to Chicago. Completed in 1859, it was a long route and involved a climb across the White Mountains, next a long trek through Canada and then passengers and freight had to be ferried across the St. Clair River from Sarnia to Port Huron. The Grand Trunk had a line from Port Huron to Detroit, but then passengers and freight switched to the Michigan Central to reach Chicago.

A different route had been completed four year earlier. It included the Michigan Central Railroad from Chicago to Detroit, the Canada Southern Railroad from Windsor, Ontario to a point near Niagara Falls and then the New York Central Railroad from Niagara Falls onto Buffalo, Albany and New York City. It was also a rather long route and required passengers and freight going to and from the Midwest to be taken off trains and put on ferries for the crossing of the Detroit River.

A shorter route—involving no foreign travel and no ferrying of cars and passengers across water—was the quest of those who invested in the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern immediately after the Civil War. Looking at a map, you might think it would be easy to build a rail line from Buffalo along the south shore of Lake Erie and then across northern Indiana directly into Chicago. Several problems arose. Thus this line became one of the later ones to link the East Coast with the Midwest. The state of Pennsylvania called for a different width between rails than New York or Ohio. And, in the 1850s and 1860, much of the area around Toledo was very swampy—a real challenge for rail builders. Furthermore, a direct line west from Cleveland to Toledo required a very expensive bridge across the wide mouth of the Sandusky River. The first lines in the area of northern Ohio went far south to skirt large Sandusky Bay.

The Lake Shore and Michigan Southern brought together a series of independent rail lines that went west from Buffalo to the Pennsylvania border, different lines across the Lake Erie corner of the Keystone State and several lines that stretched east from Cleveland toward Pennsylvania. There was another array of actually built and planned rail lines going west from Cleveland that avoided the most expensive construction problems and reached Toledo on a circuitous but dry routes.

How could the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern get from Toledo to Chicago? Eventually, they built a direct line across the flat plains of western Ohio and northern Indiana but, in 1869, they lacked the capital for such a substantial construction project. Here is where the name Michigan Southern comes in.

Michigan’s first governor, Steven T. Mason, convinced the legislature in the late 1830s to issue bunds to support three great transportation projects that would boost the state’s economy and population by linking Michigan to the nation. The most successful of these was the rail line that stretched west from Detroit. Construction started in February, 1838 and the line reached Chicago just 14 years later. Mason, however, also proposed a rail line across the southern tier of counties from Monroe on Lake Erie to New Buffalo on Lake Michigan. The economic crash of 1837 pretty much ended state-supported rail building in Michigan. Some miles of the southern tier route were completed with the line reaching Adrian in 1840 and Hillsdale in 1843. Facing immense financial difficulties, the state sold their minimally financed railroads in the 1840s. Private interests took over the southern route but also faced a shortage of capital. Gradually they built west through Jonesville, Coldwater, Sturgis and White Pigeon. By the late 1840s, it became clear that, while shipping by water was inexpensive, an all-rail line across Michigan would be cheaper and more efficient than taking Michigan products and passengers to a port on Lake Michigan where they would have to change to a Chicago-bound boat. And ships, of course, could not ply the Lake from about mid-December to late March. The management of the Michigan Southern realized that an Indiana railroad went directly from Elkhart, Indiana to the Illinois border. So, rather than building their own line on to New Buffalo or another Lake Michigan port, they built to the Indiana state line and then arranged for a subsidiary to connect their southern tier line to railroad that already extended from Elkhart to Chicago. By 1852, this line linked the southern counties of Michigan and to Chicago.

In 1836, interests in Toledo funded the building of a railroad west from their city with the aim of reaching the Kalamazoo River. Originally, this was the Erie and Kalamazoo line although it never reached Kalamazoo. By November, 1836, however, the line connected Toledo with Adrian, Michigan. This was the first railroad in the state to operate, although its first “trains” were pulled by horses along wooden rails. This line from Toledo to Adrian was included in the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railroad. Thus the L. S. & M. S. established a rail route from Buffalo to Chicago, but one that went through southern Michigan—not very direct but effective since it did not involve taking passengers and freight off a train on onto a ferry to get from the east coast to the Midwest.

The Vanderbilt family was interested in monopolizing much of the eastern railroad business, particularly all shipping from the New York and Boston ports to the Midwest. The Vanderbilts may have had financial influence in the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern since its inception in 1869. By 1877, the Vanderbilts purchased enough stock to control the railroad. Quite quickly, they had the capital to build a Toledo to Chicago road bed that was much more direct than the one through Adrian, Hillsdale and White Pigeon.

The 1870s were years of a tremendous rail building activity in Michigan. The Civil War called for many manufactured goods, goods that could be assembled using the white pine from the forest that covered the state. People began to realize that railroads were greatly transforming the way transportation worked in this country and propelling the shift from agriculture to manufacturing. Almost all cities and hamlets feared that they would be isolated and would wither away if they did not have a rail link to the outside world.

By the time of the Civil War, a collection of small factories emerged along the banks of the Grand River in what is now called the Old Town section of Lansing. This website describes the history of this area in: Lansing’s Old Town: Industry by the River. Factories used water to power their equipment and this explains why towns along rapidly flowing rivers developed in Michigan in the years when manufacturing was emerging in this state. A rail connection was needed to export the products made in the early factories of this village. The Lake Shore and Michigan Southern, similar to other lines, wished to add branches that would generate traffic for its main line that connected New York to the Midwest. Thus, this rail line began building a line north from Jonesville—very near Hillsdale. The rails reached Albion in January, 1872 and Eaton Rapids in September of that year. By January, 1873, the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern reached North Lansing. This is the furthest north point ever served by this railroad. Hillsdale was a major junction point for the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern so passenger trains on this line went back and forth from Lansing to Hillsdale where passengers might connect to trains headed for Chicago, Buffalo or New York.

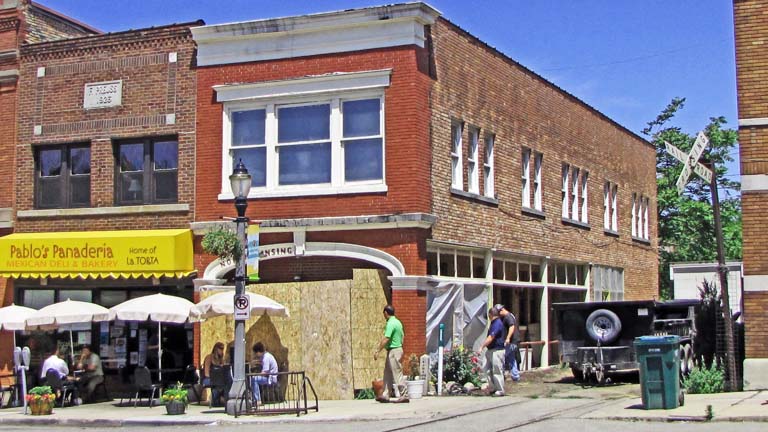

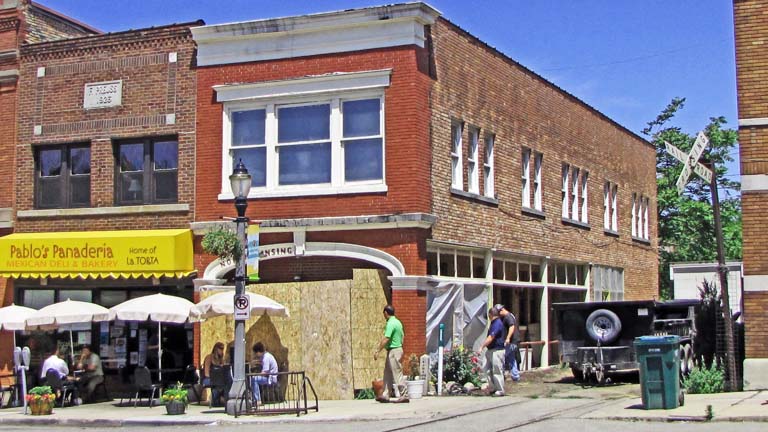

The depot you see pictured above is a very small and unusual one. I presume that the railroad could not easily acquire land for a more appropriate depot. The Vanderbilts not only controlled the Lake Short and Michigan Southern but also the Michigan Central. The Michigan Central and Pere Marquette invested substantial funds in an attractive modern Lansing Union Depot—not more than a mile away from North Lansing. The railroad owners may have seen little need for a separate depot for the Lake Shore and Michigan.

In 1914, the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern disappeared as a corporate entity and became part of the New York Central Railroad. The same thing happened to the Michigan Central in 1929. The few passenger trains operated by Lake Shore and Michigan Southern moved into the Lansing Union Depot in 1917.

Business on branch line railroads in Michigan fell substantially in the 1920s as the state’s new highway system allowed motor vehicles to efficiently move people and freight. As the post office shifted their business from the rails to trucks, branch line passenger trains became a great financial drain. The economic catastrophe of the 1930s further reduced the use of railroads. In 1941, the New York Central abandoned the line from North Lansing to Eaton Rapids and, subsequently, abandoned almost all of the line that had been built from 1871 to 1873.

Architect: Unknown to me

Date of construction: Presumably circa 1900

Use in 2012: Empty building undergoing renovation

Book describing the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern: Bill Warwick, Dave McLellan and Ginger Riehle (editors), Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railway (Transportation Trails, 1989)

State of Michigan Registry of Historic Sites: Not listed

National Register of Historic Places: Not listed

Photograph: Ren Farley; June 6, 2012

Description prepared: June, 2012

Return to Transportation

Return to Homepage