After the Revolutionary War, the United States assumed they possessed the land west from the crest of the Alleghenies to the Mississippi River. The British, however, maintained their fort at Detroit and, from time to time, encouraged Indians to attack the many settlers who crossed the Alleghenies and sought to homestead in what became Ohio and Indiana. Eventually, President Washington determined that he was forced to send troops into Ohio to fight the Indians. At the Battle of Fallen Timbers, United States troops defeated Indians who received at least minimal support from the British. This hastened the drafting of Jay’s Treaty, a document that led the English to relinquish their claims to land in the Northwest Territories. On July 11, 1796 the British peacefully surrendered their fort to forces. Colonel Jean François Hamtramck and then Captain Moses Porter raised the Stars and Stripes in Detroit for the first time.

In the first decade of the Nineteenth Century, the United States became increasingly unhappy with England for many reasons. A major one concerned international shipping. The United States believed that the nation’s bottoms should be able to carry out trade wherever they wished, but the British sought to control trade in the North Atlantic, so their Navy frequently intercepted US ships. In addition, the British Navy regularly impressed seamen from US ships; that is, they forcefully removed sailors and forced them to serve on British ships against their will.

In the first decade of the Nineteenth Century, the United States became increasingly unhappy with England for many reasons. A major one concerned international shipping. The United States believed that the nation’s bottoms should be able to carry out trade wherever they wished, but the British sought to control trade in the North Atlantic, so their Navy frequently intercepted US ships. In addition, the British Navy regularly impressed seamen from US ships; that is, they forcefully removed sailors and forced them to serve on British ships against their will.

President James Madison sought to rectify matters by starting a war against England in 1812. He believed that United States forces could easily invade and control sparsely populated and weakly defended Canada. Because of the serious threat that Napoleon posed to the British in Europe, President Madison assumed that the British could not and would not send many experienced soldiers to defend Canada or invade the United States. Madison thought that once the United States controlled Canada, the British would quickly sue for peace. He would propose that the United States military would leave Canada if the British promised to respect the rights of US bottoms to sail the high seas. He thought that a short war would be a successful one and would ensure the continued independence of his nation.

In April, 1812, President Madison convinced Congress to declare war against Britain, a war that was not popular in quite a few parts of the United States, especially New England. Once war was declared, the British became increasingly active in supporting Indian tribes in the Midwest who would fight for them against the United States. In the summer of 1812, Indians—with some support from the British—rather easily overran the United States forts at present-day Chicago and at the Straits of Mackinac. Former Michigan Territorial Governor William Hull, who had led troops in the Revolutionary War, was appointed by President Madison as Brigadier General in charge of the Army of the Northwest headquartered in Detroit. By August, 1812, Hull knew of the American losses of Fort Dearborn and at Mackinac and believed that he was threatened by a large force of Indians led by Chief Tecumseh along with British and Canadian soldiers who would soon attack and likely overrun Detroit. Undoubtedly, he recalled the 1763 siege of his city led by Chief Pontiac. Without engaging in any warfare, Brigadier General Hull surrendered Detroit to the British on August 16, 1812. Subsequently, he received a court martial for giving up Detroit without a battle. The next year, a court martial found him guilty of cowardice and neglect of duty and ordered his execution. President Madison later commuted his death sentence.

British and Canadian soldiers who would soon attack and likely overrun Detroit. Undoubtedly, he recalled the 1763 siege of his city led by Chief Pontiac. Without engaging in any warfare, Brigadier General Hull surrendered Detroit to the British on August 16, 1812. Subsequently, he received a court martial for giving up Detroit without a battle. The next year, a court martial found him guilty of cowardice and neglect of duty and ordered his execution. President Madison later commuted his death sentence.

With General Hull no longer in command, American forces Brigadier General James Winchester was named to replace General Hull. Winchester led troops in the Revolutionary War but proved to be very unpopular with his peers and with his soldiers in 1812, so he was very quickly replaced by Major General William Henry Harrison. Harrison had a record of great accomplishments in fighting Midwestern Indians, especially in Indiana and was later elected President. He took control of Army of the Northwest but appointed 60-year-old James Winchester as his second in command.

Many of the troops that Harrison and Winchester commanded were volunteers from Kentucky. Governor Isaac Shelby of that state had fought in the Revolutionary War and was an extremely strong supporter of the War of 1812 for reasons that I do not understand. He effectively recruited many young men from Kentucky and sent them north to prepare for the planned invasion of Canada. Given that there were no roads across Ohio, it was quite an accomplishment for Kentucky soldiers to reach the Detroit theater.

General Harrison realized the blunder General Hall made and made plans to drive the British from Detroit as part of the planned  eventual invasion of Canada. He made tentative plans to do so during the winter of 1812-1813. While he was assembling and training his forces, he ordered that General Winchester bring his Kentucky troops as far north as Fort Meigs, located near present-day Toledo and where the Battle of Fallen Timber had been fought. His forces would be held in reserve, ready to march north toward Detroit should General Harrison need them.

eventual invasion of Canada. He made tentative plans to do so during the winter of 1812-1813. While he was assembling and training his forces, he ordered that General Winchester bring his Kentucky troops as far north as Fort Meigs, located near present-day Toledo and where the Battle of Fallen Timber had been fought. His forces would be held in reserve, ready to march north toward Detroit should General Harrison need them.

Apparently, General Winchester was not one to strictly follow orders. When he arrived near the mouth of the Maumee, he presumed that the British had a very weak line of defense south of Detroit and that he could easily move north and recapture Detroit. At this time, there were few good roads in the marshy area between the Maumee and Detroit. Winter was the best time for an invasion since the land and waterways were frozen.

French settlers from the Windsor and Detroit areas sought to expand their farming area. By 1770, they realized that acreage near present-day Monroe was rich and blessed by a rapidly flowing river that made the location accessible. Indeed, the French knew that productive grape vines lined the waterway, so they named the waterway River Raisin, a name it continues to bear. When General Winchester thought about invading Detroit in early 1813, Monroe was a French settlement known to US residents, not surprisingly, as Frenchtown.

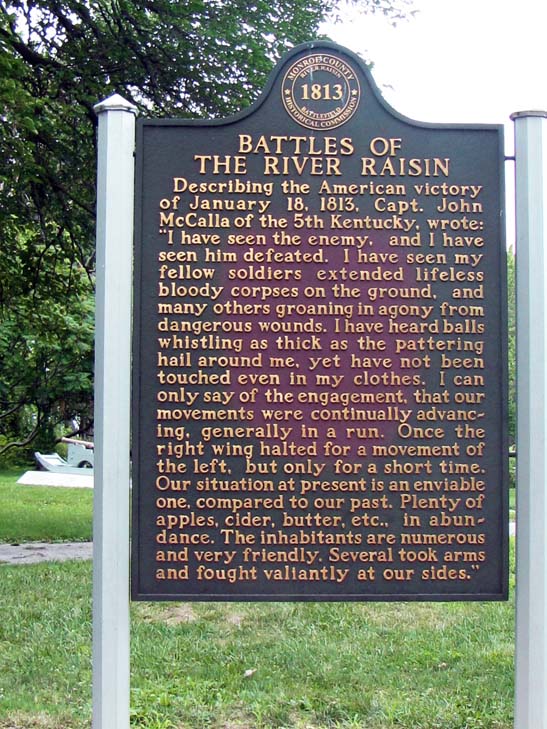

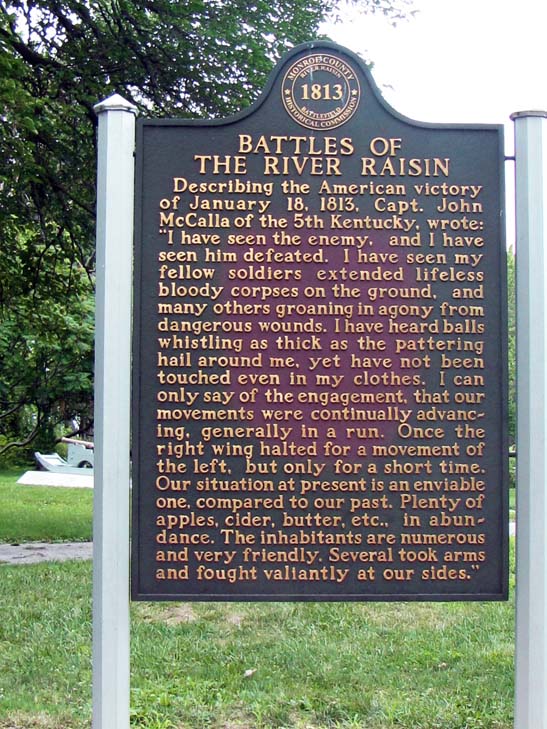

General Winchester had Colonel William Lewis lead a force of 667 Kentuckians against a small fort near Frenchtown held by 63 British soldiers along with about 200 Potawatomie Indians. Colonel Lewis’ forces attacked on January 18, 1813 and quickly routed their enemy. This was the First Battle of the River Raisin, won by the United States.

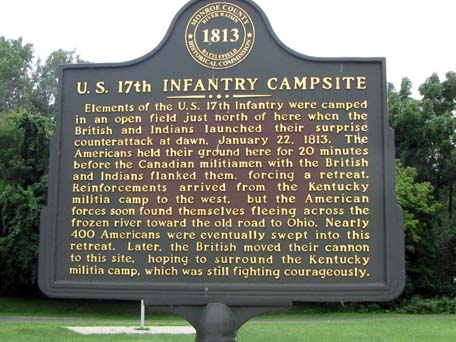

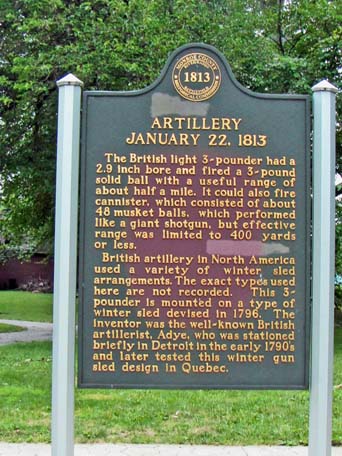

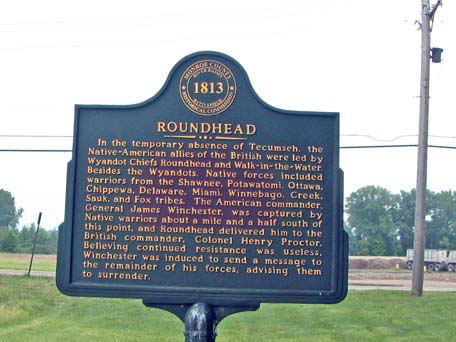

General Winchester learned of this battle and presumed that it was a good time to invade Detroit, even though he had no orders instructing him to accomplish this. He arrived at Frenchtown along with many additional forces and some supplies. However, British Brigadier General Henry Proctor, who commanded British forces in this theater, had his own plans. When the British surrendered Detroit to Hamtramck in 1796, they built Fort Malden at present-day Amherstburg, Ontario. In January, 1813, the Detroit River was frozen. Proctor quickly assembled an army of 597 British regulars and about 800 Indians and marched them close to Frenchtown, apparently unknown to General Winchester. However, Chief Tecumseh was not in command of these Indians.

Before sunrise on January 22, the British attacked. Many or most of the Kentucky volunteers did not have battlefield experience and were ill-prepared for combat. They did not effectively repel the advances of experienced British fighters and may have lacked the supplies and munitions they needed. This second battle of River Raisin was a quick one but a major defeat for the United States. By the end of the day, the fighting was over. The official count of United States casualties in the Second Battle of the River Raisin was 397 killed and 27 wounded. 547 were taken prisoner by the British. In essence, General Winchester, who was taken prisoner, lost his army in less than one day of fighting.

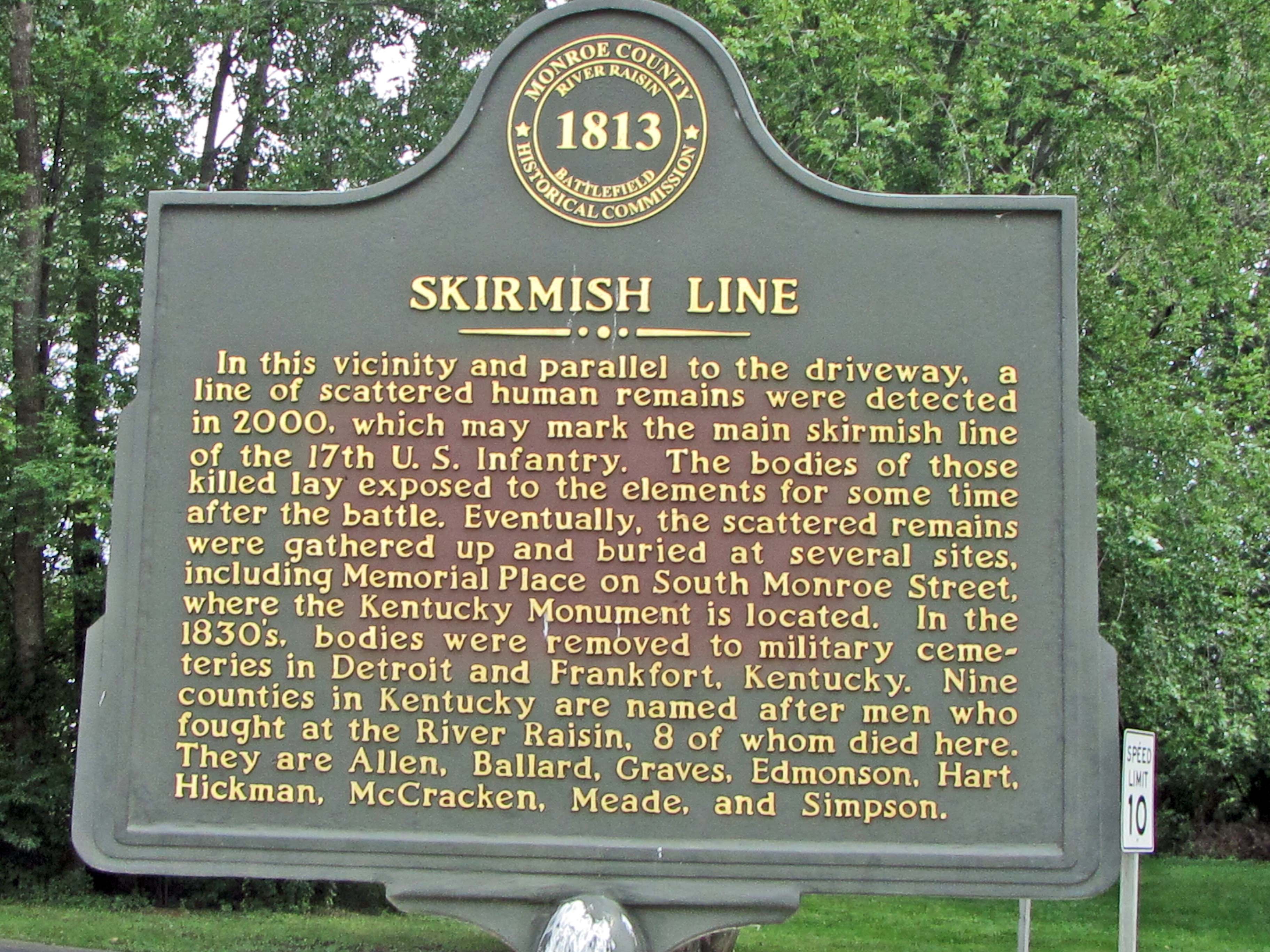

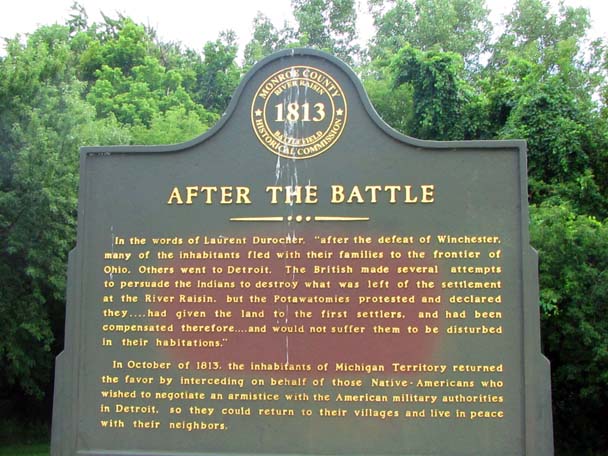

Brigadier General Proctor feared that General William Henry Harrison might quickly assemble a large force that would retaliate for the massive American defeat. Having won the Battle of River Raisin, General Proctor retreated with his warriors to nearby Fort Malden. The British were ill prepared to take so many Americans captive. Those Kentucky soldiers who were able to walk were marched to Fort Malden, but those who were injured were left on or near the battlefield in Frenchtown. This led to what is known as the River Raisin Massacre. The Native American allies of the British, on the morning of January 23, began robbing and pillaging the injured Kentucky soldier who had been left behind by the British and burned the buildings where they sought shelter. Perhaps 30 to 100 American soldiers died in this massacre. Nine Kentucky counties carry the name of officers who fought at the Battles of River Raisin. Only one of those nine individuals survived the warfare.

General Winchester fared much better than General Hull. After being imprisoned by the British, General Winchester was released and then went on to serve with Andrew Jackson in 1814 in his battles against the British on the Gulf Coast in the final days of the War of 1812.

On September 10 1813, United States Navy forces under the command of Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry devastated the British Lake Erie fleet. General Proctor surrendered Frenchtown, Detroit and Fort Malden without a fight. On September 29, 1813, General William Henry Harrison led US forces into Detroit and the city has remained in the United States since then. General Harrison then invaded Canada. General Proctor made his stand at the Thames River approximately fifty miles to the east of Detroit in southern Ontario. By this time, Governor Isaac Shelby of Kentucky was on the battlefield with his troops. On October 5, 1813, General Harrison soundly defeated the British and Canadian forces in the Battle of Thames. Tecumseh lost his life in this conflict.

The War of 1812 continued through the summer of 1814 with neither side winning definitively and both sides becoming tired of the bloody and costly fighting. On December 24 of that year, representatives of the United States and Britain signed the Treaty of Ghent, ending the war. The British agreed to minimize their disruption of US shipping and withdrew from the parts of Maine that they had occupied.

On March 30, 2009, President Obama signed legislation permitting the National Park Service to administer the River Raisin Battlefield. The National Park Service has designed 11 National Battlefields, one National Battlefield Site and nine National Military Parks. The legislation that President Obama signed may permit one of these designations for the River Raisin Battlefield.

State of Michigan Register of Historical Sites: P24, 247 Listed February 18, 1956

National Register of Historic Places: Listed: December 10, 1982

Website: http://www.co.monroe.mi.us/government/departments_offices/museum/river_raisin_battlefield.html

Website: http://www.riverraisinbattlefield.org/

Books: Donald R. Hickey, Don’t Give Up the Ship! Myths of the War of 1812. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2006

Walter R. Borneman, 1812 The War that Forged a Nation. New York: Harper Collins, 2004

Photograph: Ren Farley; July 27, 2010

Description prepared: August, 2010

Return to Historical Informational Markers

Return to Military Sites

Return to Home Page