James Mitchell Ashley was one of many prominent Michigan railroad builders in the late Nineteenth Century, but the way he got into railroad construction distinguishes him. He has, perhaps, greater significance in the nation’s history. Ashley was born near Pittsburgh in 1824. His father was a bookbinder but many in his family were ministers. Apparently, his father insisted that Ashley also become a minister but Ashley refused. He ran away from home as a teenager, worked as a printer in Portsmouth, Ohio. Later he studied law and became a member of the Ohio bar in 1849. Then he moved to Toledo in  1851 to run a drugstore.

1851 to run a drugstore.

Ashley was an ardent abolitionist and realized that the new Republican Party would, cautiously, welcome members who shared his strongly held views about the need to promptly end human bondage in this country. He accepted the Republican Party’s nomination to run for Congress and represented Toledo in the lower house for five terms from 1859 to 1869.

Congressman Ashley wrote and then tended to the passage of a law in 1859 that prohibited the sale of slaves in the nation’s capital. Abolitionists were upset that humans were sold at a market located very close to where Congress met. After President Lincoln issued his Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, he needed an ardent and capable member of the lower house to write a constitutional amendment and insure its passage by Congress so that states could ratify it. James Ashley was selected for that task so he is the principal author of the Thirteenth Amendment that ended slavery.

President Andrew Johnson needed a territorial governor for Montana in 1869. He nominated James Ashley but Congress sat on that nomination so President Johnson gave Ashley a recess appointment. The Republicans in Congress appeared to despise almost every action taken by President Johnson. Indeed, the peak levels of conflict between the legislative and administrative branches of government may have occurred during the Johnson years. There was so much opposition to his appointment that James Ashley gave up his appointment in Montana after serving less than a year and returned to Toledo.

Government pension and retirement programs were not generous at that time so Ashley had to make money. Railroads were the dynamic business of that era and many investors were becoming prosperous by building and investing in railroads or by promoting and trading financial instruments linked to new rail lines. In the mid-1870s, the residents of Ann Arbor felt they were being exploited by the high rates of the Michigan Central. Virtually all persons going to that city and all products entering or leaving Ann Arbor were carried on the tracks of the Michigan Central. A group of Ann Arbor investors began to build a railroad to Toledo where it would connect with other rail lines and, perhaps, force the Michigan Central to reduce rates.

Ashley saw an opportunity and began raising funds for the Ann Arbor Railroad. He was certainly an expansionist and in the course of 15 years he built a 300 mile line that arced across the Lower Peninsula from Toledo to the port of Frankfort on Lake Michigan. In 1893, he had large steamships built to serve as ferries that would transport rail cars across Lake Michigan giving customers a way to avoid the tremendous congestion that greatly delayed rail traffic passing through Chicago.

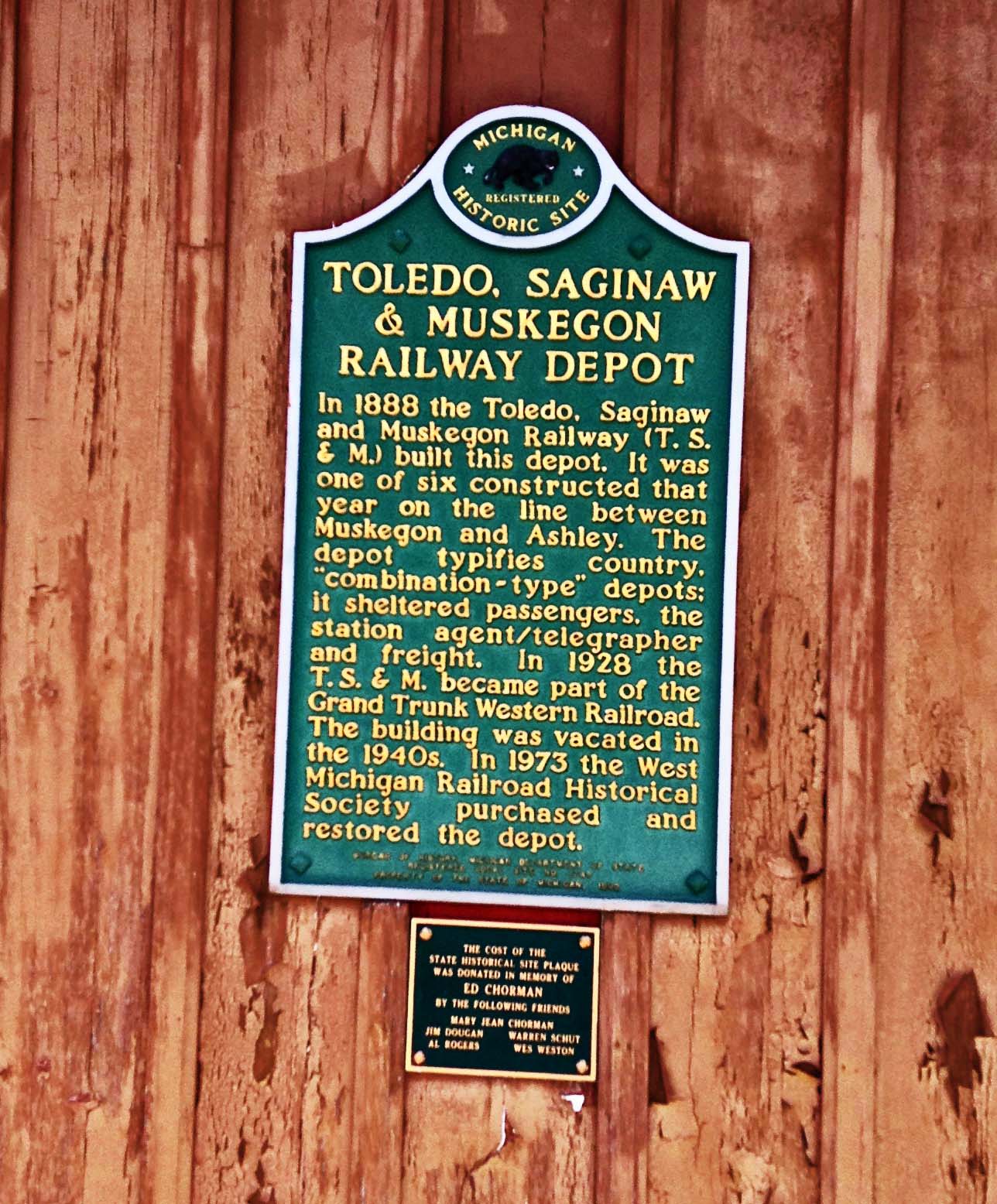

Just the Ann Arbor line wa s not enough for James Ashley. He, apparently, gave some thought to building a rail line into the Thumb but by the time he got around to that endeavor, lumbering and forest fires had removed most of the valuable timber from that area. In the mid-1880s, James Ashley found a lumber baron in Saginaw, Ammi W. Wright, who was also interested in profiting from the railroad boom. They apparently raised fifteen million dollars and decided to build an east-west line across Michigan from a point on Ashley’s Ann Arbor Railroad to the port of Muskegon. In just two years, 1887 and 1888, they constructed a 96 mile line stretching across the state to Muskegon. The largest city, other than Muskegon, on this line was Greenville. This was named the Toledo, Saginaw and Muskegon Railroad, presumably because of the home towns of the two major investors. The junction point of this new line and the Ann Arbor was located 21 miles north of Owasso. Conveniently, the residents of that hamlet changed the name of their village to Ashley when it was chosen to be a railway junction. It retains that name today but, so far as know, there is no historical marker in Ashley commemorating Ashley.

s not enough for James Ashley. He, apparently, gave some thought to building a rail line into the Thumb but by the time he got around to that endeavor, lumbering and forest fires had removed most of the valuable timber from that area. In the mid-1880s, James Ashley found a lumber baron in Saginaw, Ammi W. Wright, who was also interested in profiting from the railroad boom. They apparently raised fifteen million dollars and decided to build an east-west line across Michigan from a point on Ashley’s Ann Arbor Railroad to the port of Muskegon. In just two years, 1887 and 1888, they constructed a 96 mile line stretching across the state to Muskegon. The largest city, other than Muskegon, on this line was Greenville. This was named the Toledo, Saginaw and Muskegon Railroad, presumably because of the home towns of the two major investors. The junction point of this new line and the Ann Arbor was located 21 miles north of Owasso. Conveniently, the residents of that hamlet changed the name of their village to Ashley when it was chosen to be a railway junction. It retains that name today but, so far as know, there is no historical marker in Ashley commemorating Ashley.

The Toledo, Saginaw and Muskegon, I believe, never owned any equipment and never ran a train. The line was leased to the Grand Trunk Railroad even before it was completed and, in 1928, that railroad purchased the paper railroad Toledo, Saginaw and Muskegon. The Grand Trunk did not have a line into Ashley so their trains used the rails of the Ann Arbor Railroad to get from their home rails in Owasso to Ashley. In 1893, the Grand Trunk ran two passengers round trips every day from Owosso to Muskegon. One of those round trips made connections with trains in Owosso to and from Detroit. You could leave Sparta at 9:30 in the morning and arrive in Detroit at 4:05. And you could leave Detroit at 10:30 in the morning and get to Sparta at 5:42. The line from Ashley to Muskegon was known and is still known among rail afficianados as the Turkey Trail.

James Ashley lost control of the Ann Arbor Railroad in a bankruptcy that followed the economic crisis of 1892 although his sons continued to participate in the management of the line following bankruptcy. I suspect that he continued to receive lease payments from the Grand Trunk Western for some years prior to his death in Ann Arbor in 1896.

Central Michigan was laced with east-west railroads that were laid down in the great building boom that ended with the economic crisis of the 1890s. When the state began constructed roads in the years after World War I, trucks and cars quickly captured the local business that railroads once had. By the state of the Depression decade, the Grand Trunk ran one passenger trains six days a week making a leisurly trip from Muskegon to Ashley in the morning and a return after lunch. This suggest they retained a mail contract. By the end of the Depression decade, service on this line was reduced to a mixed train that departed from Muskegon at 7 on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays and had a scheduled 1 PM arrival time in Durand. On Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays, you could leave Durand at 6 on this mixed train, arrived in Sparta at 1:25 in the afternoon. Or you could stay on the leisurely train and get to Muskegon just before 3 PM. This suggest they retained an express contract but had lost the mail contract. This line through Sparta was among the earlier east-west lines in Michigan to be abandoned. It survived through World War II when gasoline and tires were rationed and no new vehicles were built but, in 1946, the Grand Trunk pulled up their tracks west from Greenville to Muskegon.

This is a rather simple board and batten depot. It has a traditional bay window that faced the tracks when there was rail service here. Alas, I failed to take a picture of that side of this depot.

Sparta is named for the township where it is located. Census 2010 counted 9010 residents of the township. Sparta was also served by the line of the Pere Marquette Railroad that stretched north from Grand Rapids to Petosky. The Pere Marquette used their own depot but it is no longer standing. That line remains intact and is now operated for freight service by the Marquette Railroad that, in 2015, operated 126 miles of track north from Grand Rapids to Ludington and Manistee.

Date of Construction: 1888

Architect, Designer or Builder: Unknown to me

Use in 2015: Apparently, this is the home of the West Michigan Chapter of the National Railroad Historical Society. But the website of the National Railroad Historical Society fails to list such a chapter, perhaps because they lack a presence on the internet.

State of Michigan Registry of Historic Sites: Listed

State of Michigan Historical Marker: Located near depot and visible from Union Street

National Register of Historic Places: Not listed

Return to Transportation

Return to Homepage