For much of the Twentieth Century, Henry Ford’s River Rouge factories were the world’s quintessential example of industrialization. That is, they were the best example of a large manufacturing firm producing a complex machine in massive quantities that owned all of the resources and facilities needed to make almost every component of that machine. The River Rouge com plex also symbolized the Fordist system of production. This is the strategy of using machines extensively, but also using personnel to perform simple tasks that anyone can learn quickly and then repeat again and again—many times an hour. As economically developed countries switched their employment base from agriculture to manufacturing, many companies and national governments looked to Henry Ford’s system as the ideal model to be followed.

plex also symbolized the Fordist system of production. This is the strategy of using machines extensively, but also using personnel to perform simple tasks that anyone can learn quickly and then repeat again and again—many times an hour. As economically developed countries switched their employment base from agriculture to manufacturing, many companies and national governments looked to Henry Ford’s system as the ideal model to be followed.

Henry Ford purchased two thousand acres along the River Rouge in 1915, apparently without any specific plans for the property. Some speculate he wanted to create a bird sanctuary. At the outset of World War I, Ford announced that his firm would never build munitions, perhaps reflecting his aversion to war and his belief that war primarily benefitted rich families who owned banks. However, when the Navy approached him about the mass production of small ships to chase German submarines, Ford agreed to do so. The federal government approached Ford because of his expertise in mass production. His Piquette Avenue and Highland Park plants were not located on a waterfront, so he began his shipbuilding on the River Rouge. This was not a success. He did not complete any ships until after World War I concluded. The Navy was unsatisfied with the few boats he constructed, leading to extensive litigation about what payments, if any, Ford would receive from the government.

Ford’s successful production of thousands of Model T’s at the Highland Park plant on Woodward led him to think about new facilities. I believe that one of his early decisions was to build farm tractor at the River Rouge plant where Ford attempted to build boats for the Navy. That endeavor was also not very successful since the nation’s agricultural sector went into economic decline in the 1920s and the market for tractors lost its bloom. By the time Ford started the mass production of farm tractors, competitors were well established.

Early in the Twentieth Century, when Ford lacked capital, he assembled cars using parts made by a variety of suppliers. The Dodge Brothers were especially important to his operation. By 1920 after he took over complete control and ownership of the firm, he took a different approach. He decided that he would maximize his control over production and his profits if he owned all the means of production. This River Rouge site became the focus of this industrial strategy. I do not know if, anywhere in the world, there was a bigger complex turning raw materials such as iron ore and copper into a mass produced durable product. The first blast furnace at this location was designed by Julian Kennedy of Pittsburgh and opened in 1920. Another blast furnace opened in 1928 and the final one in 1948. To supply those mills, Ford widened the River Rouge and created turning basin so that the Great Lakes bulk carriers he owned could transport iron ore, limestone and other ingredients to the mill. Ford owned forests in the Upper Peninsula for his lumber bu t, so far as I know, he did not purchase any iron ore or limestone mines. Ford also purchased coal mines in Kentucky to supply energy for his mills and his huge power plant. He also bought the Detroit, Toledo and Ironton Railroad to control the cost of getting his coal from his mines to his factory on the Rouge.

t, so far as I know, he did not purchase any iron ore or limestone mines. Ford also purchased coal mines in Kentucky to supply energy for his mills and his huge power plant. He also bought the Detroit, Toledo and Ironton Railroad to control the cost of getting his coal from his mines to his factory on the Rouge.

It is difficult to summarily describe this complex. Apparently, it included a maximum of 93 buildings with 100 miles of railroad track and 15 miles of paved roads. The principal features were steel furnaces, coke ovens, rolling mills, a glass factory, a tire plant, a stamping plant, a tool making facility, a soybean conversion plant producing plastic components and an electric generation plant that may have produced enough power to supply much of the city of Detroit. Not all of these plants were in operation simultaneously since some of Henry Ford’s experiments proved unsuccessful. From time to time, Ford also found it cheaper to buy components than manufacture them.

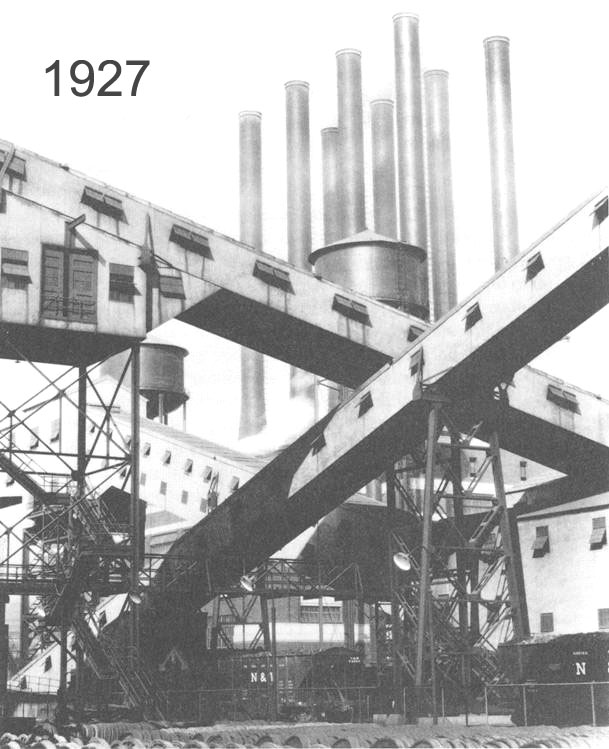

Vehicles were not assembled at this location until 1927 but then production increased rapidly. At peak, this River Rouge plant turned out a new vehicle every 49 seconds. During World War II, total payroll at the plant may have reached 100,000.

One of the largest facilities on this campus is the Steel Operations Building designed by Albert Kahn and opened about 1926. This includes the Steel Mill Plant and the Dearborn Stamping plant. This is a building one mile in length covering 72 acres. It includes parts of a variety of other industrial building designed by Albert Kahn including the Open Hearth Building, the Pressed Steel Building, a Rolling Mill and a Spring Building.

From the 1920s to World War II, economic development specialists and industrialists from around the world visited the Rouge plant to learn about the advantages of integrated production. And those many critics who believed that modern industrialism degraded workers and forced them to become mindless appendages to machines, also visited. Undoubtedly, the photographs of Charles Schiller dating from the late 1920s popularized the plant. He was the artist who first realized that photographs of modern manufacturing industries merited inclusion in the leading art galleries.

The energy price crisis of the 1970s, the severe economic downtown of the early 1980s and competition from European and Asian car markers helped to reduce employment at River Rouge. Needing financial support, the River Rouge steel mill was sold in 1989 along with about one-half of the Ford acreage here. The Great Lakes steamers and the complex’s railroad were also sold as the Ford Corporation raised cash by selling its assets. By 1992, only the Ford Mustang was assembled at River Rouge and it appeared that this colossus might close.

The United Auto Workers union and Ford’s management agreed to substantial changes in the late 1990s. Ford renovated the Dearborn Engine plant, and later built a massive new assembly plant for the most popular single model sold in the United States, the Ford F-150 pickup truck. The Rouge steel mill was sold to the highly successful Russian conglomerate, Severstal. They invested heavily in modernizing the mill and making it environmentally sound. It is now an efficient, modern mill, but not controlled by Ford.

It is difficult to forecast the outlook for any major industrial operation in the auto industry. However, the Rouge campus with its modernized steel mill and new truck plant appears to be in a much more favorable position now than it was in the early- or mid-1990s.

Date of Construction: The steel production facility dates from 1919

Architect: Many architects but Albert Kahn and his firm were the chief designers

Use in 2010: Steel plant and truck production factory

Books: Joseph Cabadas, River Rouge: Ford’s Industrial Colossus (St. Paul, Minn.: Motorbooks International, 2004)

Bryan R. Ford, Rouge: Pictured in Its Prime: 1917-1940. (Dearborn, Mich.: Ford Books, 2003)

State of Michigan Registry of Historic Sites: Listed December 14, 1976.

National Register of Historic Places: Listed June 2, 1978

National Historic Landmark: Listed June 2, 1978

Description Updated: July, 2010

Pictures: Ren Farley

Return to Michigan Historic Landmarks