When the French crown granted land in Detroit in the 18th century, they used a ribbon system. Each owner obtained a swath about one-quarter mile in width extending northwest from the Detroit River for a mile or more. The land holder had access to fresh water and to a location where his products might be loaded on a vessel. Ribbon farms were laid out on both sides of what is now downtown Detroit. A few street names honor the French families who were granted land, including Riopelle, Rivard, St. Aubin and Campau. I do not know if Chene commemorates trees or a family. Among the most productive farms were those located just north of downtown. When U. S. settlers arrived in the 19th century, they named the area Black Bottom because of its productivity.

The African-American population of Detroit grew slowly until World War I. The French settled the Caribbean about two hundred years before they came to Detroit. They imported Africans to labor on their plantations in Guadeloupe and Martinique. French men married or cohabited with African women, leading to a French-Caribbean black population who traveled and worked throughout the North American French empire. Chicago was founded in 1781 by a French-African-Caribbean fur trader, Jean Baptiste Point du Sable. At least a few black Frenchmen lived in Detroit before the arrival of the British. There was also a small enslaved black population in the early years of the Michigan territory. During the 1830s, 1840s and 1850s, modest numbers of fugitive slaves and some free blacks either passed through Detroit or settled in the city. As Detroit’s manufacturing firms boomed in the late 19th century, some of the fugitive slaves who had migrated to Ontario or their children returned to Michigan, but the arrival of many blacks awaited the labor shortages of World War I.

Blacks who came to Detroit readily found employment in factories during the Great War. Indeed, Detroit’s Urban League had agents meeting trains to direct black men from the South to employments in the city’s factories. Black migrants found they were few places they could live. Before this migration, very small black elite worked at rewarding jobs. A few of them were educated professionals. Apparently they faced few restrictions about where they could live and, some of them attended church with whites and had whites as clients. A somewhat larger and less extensively educated black population worked in the service trades and lived in low-cost housing along side European immigrants. With World War I, came Jim Crow policies in housing. Although black lawyers such as Walter Sowers, whose home is a Michigan State Historical Site, fought diligently for equal opportunities in housing, by 1919 African-Americans who moved into white neighborhoods faced great hostility culminating in the 1926 violence that followed Dr. Ossian Sweet’s purchasing a home on Garland. .

Black migrants to Detroit found themselves confined to East Side neighborhoods, primarily along Hastings Street. In addition, there was a neighborhood near St. Cyprian’s Episcopal Church on 28th Street on the West Side where blacks could live free of white intimidation. The East Side area became the commercial center for the city’s burgeoning black population. Businesses developed to serve the needs of the city’s increasingly prosperous black population. Black doctors, lawyers, real estate brokers and merchants located there. As the black population increased, the northern boundary of the black residential district moved further and further away from the center of the city. What had once been a largely Jewish neighborhood extending along Hastings from Gratiot to Warren became, by the 1930s, a largely black neighborhood. By 1940s, blacks were moving as far north as East Ferry.

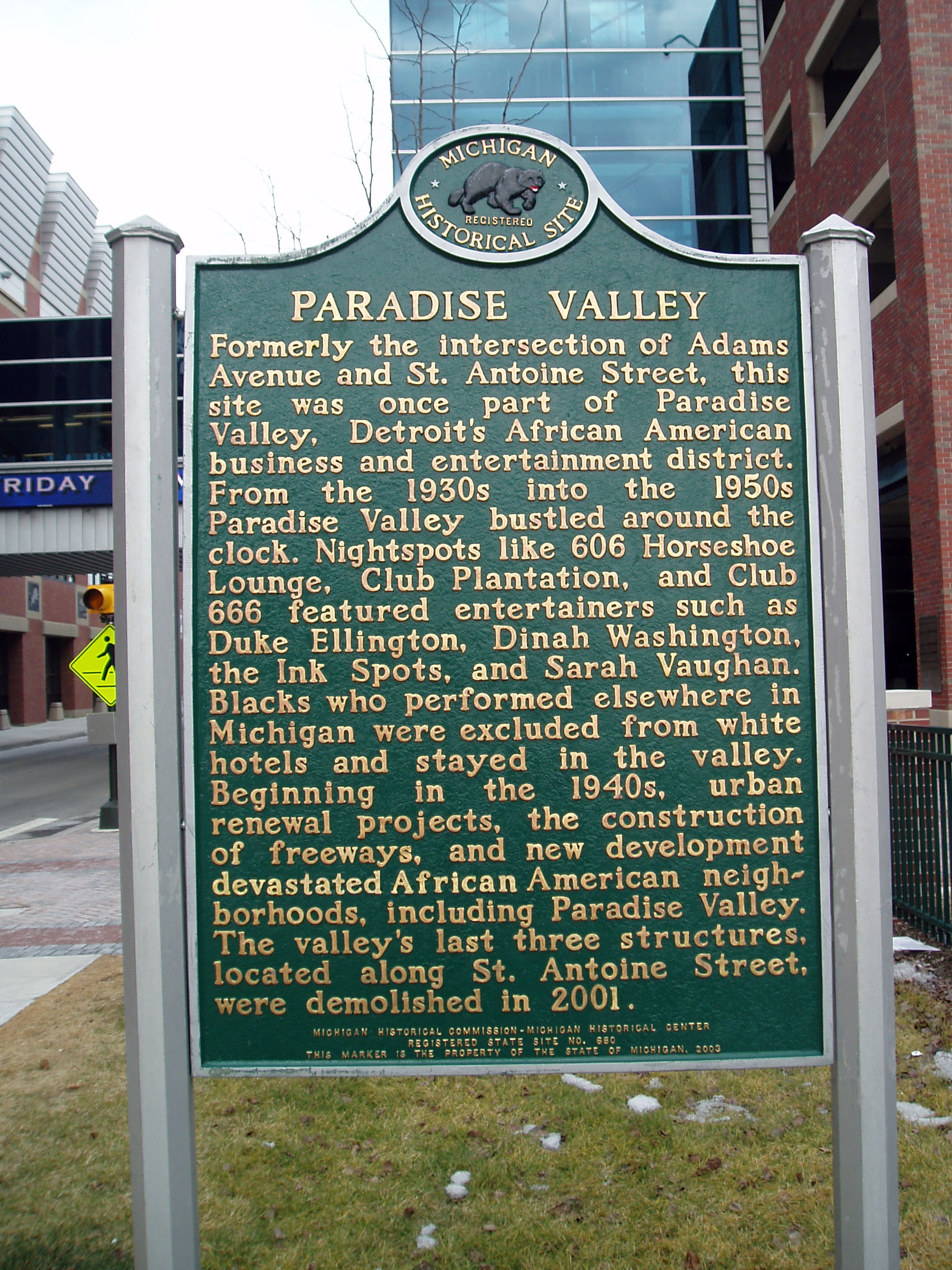

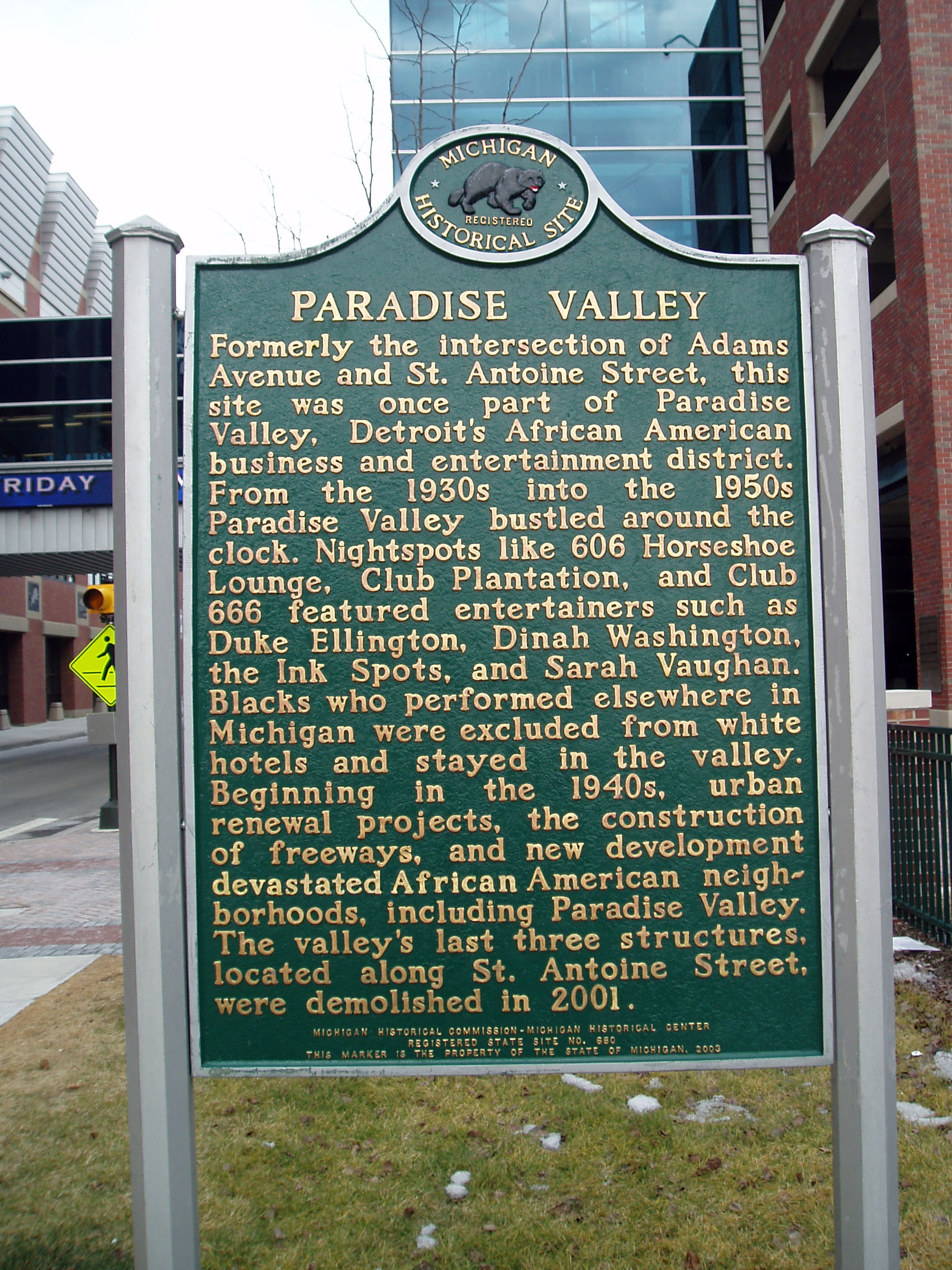

This black area became known as Paradise Valley by the 1920s. I do not know the origin of that term, and I realize that some experts on the city’s black history would reserve the term Black Bottom for the section of Hastings and adjoining streets south of Gratiot, while using Paradise Valley to describe the area north of Gratiot. During the vehicle boom of the 1920s, many black families prospered. This not only fostered the growth of a robust black entrepreneurial group, but also the emergence of a lively entertainment district. Detroit artists made major contributions to the development of jazz, and so a series of clubs in Paradise Valley attracted the nation’s most talented performers. Numerous drinking spots and clubs were known as “Black and Tan” meaning that both white and black clients and performers were welcome. Public housing in this country was built on a racially segregated basis. The Brewster Homes Project—dating from 1935—was the nation’s first major housing project for the poor and eventually included 17 high rise buildings. Since no other neighborhood in Detroit would allow such a massive concentration of blacks, it was located very near Hastings Street.

Very many favorable comments have been written in the last few years about the vitality of Paradise Valley, the prosperity of its business people, the creativity of its musicians and the dynamic black community that emerged there, despite the Jim Crow practices that pervaded Detroit. Nevertheless, most of the homes were rather flimsy. The Depression had particularly devastating consequences for blacks in Detroit who, for the most part, had few savings or resources to draw upon. The area was densely populated and probably had one of the higher death rates in the city. Criminal activities were also common. No authoritative history has been written of the liquor trade in Detroit during Prohibition, but descriptions of Paradise Valley suggest that some businessmen prospered selling liquor, managing the numbers business and by engaging in the commercial sex industry.

After World War II, city planners hoped to encourage middle-class people to remain in the city. At the same time, Detroit planners realized the need for a much better transportation system for the region. They did not have the financial resources to build rail lines or subways. Substantial federal funds became available to large US cities in the 1950s. Recognizing that many urban neighborhoods contained dilapidated, cheaply built, wooden homes dating from the 19th century, the federal government made urban renewal monies available so that cities could clear land. While Congress appropriated monies for much-needed urban renewal, this program was universally known in the black community as Negro Removal. Black neighborhoods near the nation’s downtowns or close to major universities or hospitals were chosen to “benefit” from the federal urban renewal dollars. Public housing dollars were also available to build projects where some of those displaced by urban renewal might live. In Detroit, the clearing of Paradise Valley wiped out a group of black entrepreneurs. President Eisenhower, whose wartime experience gave him a tremendous appreciation for the marvelous German highway system, made federal funds available to construct expressways. In Detroit, planners designed the Chrysler Freeway (I-75) so that it almost directly followed the track of Hastings Street. The black population of Detroit did not have the political clout to prevent the destruction of Paradise Valley. Indeed, no consideration was given to renewing the area or preserving a section since “Negro removal” was then accepted as an appropriate and desirable urban planning. In truth, many of the structures were not worth rebuilding. Most of the Paradise Valley neighborhood was razed in the 1960s and 1970s. In fairness to planners, a section of Paradise Valley was destroyed for what became the Mies Van der Rhoe historic district. A modest amount of very attractive, reasonably priced, integrated housing was built in the former Paradise Valley area.

So far as I know, there is no book describing the history of Paradise Valley and its destruction. Kevin Boyle’ Arc of Justice: A Saga of Race, Civil Rights and Murder in the Jazz Age (Henry Holt, 2004) recounts the strategies that were developed to keep Detroit’s neighborhood racially segregated. Lars Bjorn and Jim Gallert’s Before Motown: A History of Jazz in Detroit (University of Michigan Press, 2001) tells us about the history of jazz in Motown, much of it occurring in clubs located in Paradise Valley. They include maps. Richard Thomas’ excellent book, Life for Us is What We Make It: Building Black Community in Detroit: 1915-1945 (University of Illinois Press, 1992) describes racial issues, especially the conflict between blacks who sought integration and those who sought to create black institutions, during the period when Paradise Valley thrived. Frank D. Rashid’s Marygrove College website: http://www.marygrove.edu/ids/Paradise_Valley.asp provides extensive information about Paradise Valley with an emphasis upon two poets who were raised in and then wrote about the area: Robert Hayden and Dudley Randall.

City of Detroit Designated Historic District: Not Listed

State of Michigan Historic Site: Listed

State of Michigan Historical Marker:

National Register of Historic Sites: Not Listed

Book: Detroit’s Paradise Valley by Ernest Borden. (Arcadia Publishing,

Images of America Series, 2003)

Photograph: Ren Farley; March 3, 2007

Description prepared: April, 2007

Return to Racial History in Detroit