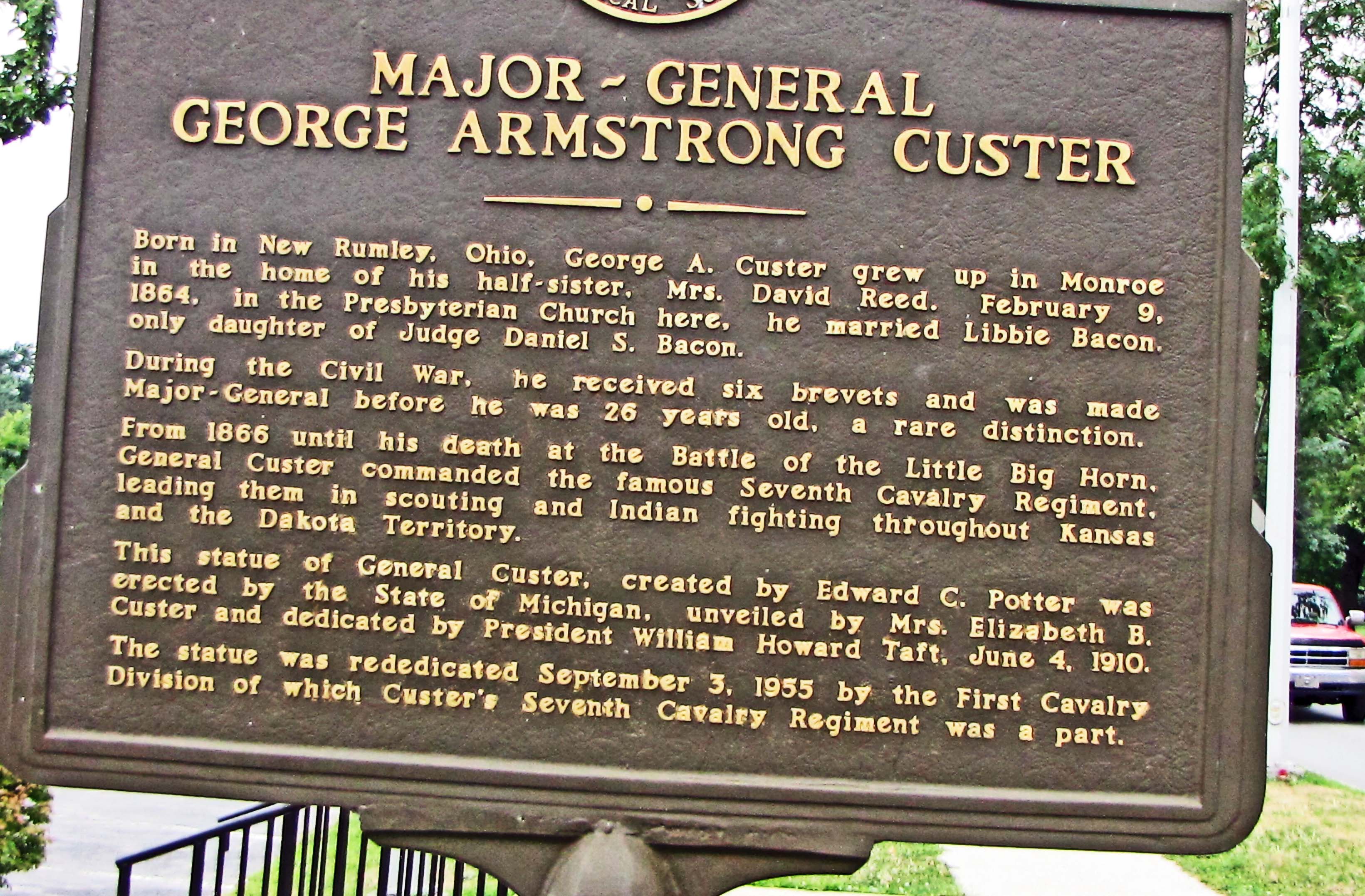

There are three great military equestrian statues in the metropolitan Detroit area. One is Henry Merwin Shrady’s portrayal of Detroit’s Civil War Major General Alpheus Starkey Williams at the intersection of Central and Inselruhe Avenue on Belle Isle. Another is Leonard Marconi’s statue of Revolutionary War hero, General Thaddeus Kosciuszko at Third and Michigan in downtown Detroit. The third is pictured above.

On December 5, 1839 George Armstrong Custer was born in New Rumley, Ohio. His father was a farmer and blacksmith; his mother, a home maker. However, he spent much of his youth in Monroe being raised by his half-sister and brother-in-law. When he reached his teens, he was sent to McNeely Normal School in Hopedale, Ohio. He graduated at age 17 and began a career teaching school at Cadiz, Ohio. Apparently, that did not greatly appeal to him, so he matriculated at West Point in 1858. Because of the nation’s need for officers, the curriculum was truncated to three years for the class of 1858. Custer graduated in 1861 and almost immediately faced enemy fire.

Custer was appointed a Second Lieutenant and led troops at the Battle of Bull Run in summer 1861, one of the first engagements of the long war. Custer distinguished himself throughout the Civil War and rose in rank. By 1863, just prior to the fighting at Gettysburg, Custer was appointed Brigadier General of Volunteers and led Michigan troops in extensive fighting for the remainder of the war. The statue you see portrays the young—24 year old—General Custer leading his forces at Gettysburg. The charge of the  Michigan First Calvary played a key role in blunting the advance of the Confederates but, in this fighting, Custer lost 257 men. The Union victory at Gettysburg was crucial to preserving the Union. In 1864, Custer led Michigan troops in fighting in the Shenandoah Valley and then moved to the east for the long siege of Petersburg, Virginia. In the final days of the Civil War—April of 1865—Custer’s forces blocked General Lee’s attempt to retreat to the South. He was present at Appomattox when General Lee surrendered his forces to General Grant.

Michigan First Calvary played a key role in blunting the advance of the Confederates but, in this fighting, Custer lost 257 men. The Union victory at Gettysburg was crucial to preserving the Union. In 1864, Custer led Michigan troops in fighting in the Shenandoah Valley and then moved to the east for the long siege of Petersburg, Virginia. In the final days of the Civil War—April of 1865—Custer’s forces blocked General Lee’s attempt to retreat to the South. He was present at Appomattox when General Lee surrendered his forces to General Grant.

Custer met Elizabeth Clift Bacon in Monroe, Michigan and wished to marry her, but her parents objected and felt that she merited a more accomplished husband. However, after Custer was appointed a Brevet Brigadier General, Ms. Bacon’s father withdrew his objections. Custer and Elizabeth Bacon married in early 1864. It seems odd from our perspective about wars today, but in the Civil War, the mothers and spouses of quite a few troops traveled to the front to be with the soldier and to nurse those who were injured. Mrs. Custer accompanied George Custer in his final year of Civil War service at many of his subsequent postings.

Immediately following General Lee’s surrender, General Custer was assigned to command Union troops that would occupy sections of Louisiana and Texas. Custer was mustered out of military service in early 1866 and returned to Monroe where he considered various employment opportunities, but apparently found none that pleased him or offered him economic security. He turned down an opportunity to travel to Mexico for employment leading troops who were seeking to overturn French rule of that nation led by the emperor they supported, Maximilian I.

The following year, Custer returned to military duty as a Lieutenant Colonel of the United States Seventh Calvary Regiment stationed in Fort Riley, Kansas. He spent most of the rest of his short life leading this unit. It was at this point, that Custer began his career as an Indian fighter.

European settlers had been fighting with Indians since the 1500s. In most cases, Indians were driven to the West by force, although very many died of European diseases and warfare. In the 1830s, President Jackson followed the popular strategy of forcing Indians to move west of the Mississippi. At this time what was known as the Great American Desert appeared to be worthless to Americans. However, railroads gradually spread into the Midwest and, by the end of the 1860s, reached across the nation. Earlier settlers found that the land was far from worthless so they established farmsteads and sought to mine valuable minerals. Indians, in many places, contested their presence and sought to forcefully remove them. The United States military then established a series of forts across the Great Plains. Various treaties were written with tribes, but in numerous cases, land that the Europeans had assumed was worthless proved to be valuable so it was settled. The settlers also assumed they had a right to make a productive use of the land since the Indians did not use the available resources. Indians often attacked the settlers so the United States military carried out campaigns during summers to confine or kill the Indians. Many of these campaigns had specific names. For the most part, they were quite bloody since neither Indians nor the US military was prepared to take and care for numerous prisoners. And the most effective way to finally end the Indian threat was to make sure there were no Indians warriors who could attack settlers. George Armstrong Custer engaged in one campaign in 1867 and another the following year. Custer led the Seventh Calvary at the Battle of Washita River near Cheyenne, Oklahoma in November, 1868, an important victory for the United States in their effort to dominate the Cheyenne. However, it is also known as the Washita massacre.

In 1873, Custer was assigned to the Dakota Territory to protect railroad survey crews who were, from time to time, attacked when they worked in Indian Territory in that region. In this role, he fought the Lakota tribe of Sioux Indians. In 1874, Custer led troops into the Black Hills and announced that he had discovered gold there. This triggered a “gold rush” and many individuals quickly went to those remote hills to seek their fortune. The Sioux, however, believed that this land was theirs and forcefully resisted the influx of whites. During 1874 and 1875, the Sioux Indians became increasingly militant about protecting their land. The level of violence increased rapidly. The Unite States military decided to conduct a summer campaign against the Sioux beginning from Fort Abraham Lincoln near present day Mandan, North Dakota in April, 1876. This was delayed, but General Custer led his Seventh Calvary out of Fort Lincoln on May 17, 1876. This was to be his final campaign. On June 25, 1876, Custer’s’ forces came upon a large tribe of Indian warriors encamped along the Little Bighorn River. Custer commanded just over 200 officers and men. His fellow commanders in the Seventh Calvary, Marcus Reno and Frederick Benteen, commanded, perhaps, another 200. The Indian force has been estimated to be as high as three thousand. The Indians won this battle and then moved quickly away. When American troops led by General Terry came upon the site of the Battle of Little Bighorn two days later, they found that all American troops had lost their lives. The nation’s centennial was being celebrated with glorious events in Philadelphia on July 4, 1876. Interestingly, this is the very day that news of Custer defeat and the loss of his army reached Philadelphia and the large population centers of the East.

Custer was a controversial figure in both life and death. There is no doubt about the contributions he made to the Union in the Civil War. The rest of his military career is not so distinguished. In each of his three years at West Point, he was threatened with expulsion for his demerits. He graduated thirty-fourth in his class, a class of 34 students. In his first year of his return to the military after the Civil War, he was court martialled for being AWOL and suspended for a year. At another point, one of his officer peers charged him with secretly marrying Monaseetah, the daughter of Cheyenne chief Little Rock, and perhaps fathering her child. Just two months before he led troops to fight Chief Sitting Bull in Montana, he was recalled to Washington and extensively questioned, although I believe this resulted from a rivalry within the military. However, there were those who argued that he should be removed from command. President Grant sharply criticized General Custer for serious military mistakes that led to his defeat at Little Bighorn but General Philip Sheridan and others defended Custer. Prior to his death, Custer had written one book defending his efforts as a warrior on the Great Plains. His widow, who outlived him by 57 years, wrote three books defending his honor and his accomplishments.

In the Nineteenth Century, Indian removal was a popular strategy. It was often justified with the argument that modern western European civilization was inevitably replacing a primitive civilization that was sure to quickly disappear. Others, including Michigan Territorial Governor Cass, rationalized Indian removal by arguing that missionaries and settlers had attempted to bring the benefits of western civilization to Indians for centuries but the Indians deliberately rejected modern values and adhered to their own ignorant, primitive practices. There were very few voices defending the Indians of the United States although President Grant—a former Detroit resident—took a more enlightened approach to Indians than his predecessors. Quite a few missionaries tried to work with the Indians, but you get the impression that many of them had a very dim view of the culture of Indians and tried to insist that they adopt European values and Christianity.

The United States military carried out campaigns against Indians for a decade after the defeat of General Custer. Finally, in the Wounded Knee Massacre in South Dakota on December 29, 1890, the military defeated Indians led by Chief Sitting Bulls’ half brother and three hundred years of warfare against Indians ended with the exception of two very small skirmishes.

The designer of this magnificent sculpture, Edward Clark Potter, was born in New London, Connecticut in 1857 and graduated from Amherst College 25 years later. He then studied at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. By the 1880s, he had decided to become an animalier—a sculptor specializing in the portrayal of animals. He went to Paris and studied for several years with the leading animaliers. When he returned to the United States, he collaborated with Daniel Chester French, arguably the nation’s most accomplished sculptor of that era. The only French sculpture in the Detroit area, the Russell Alger Memorial Fountain in Grand Circus Park, is pictured on this website. Potter most famous accomplishments are the lions that confront all who enter the Public Library in New York City. There is one other link between the statue pictured above, this sculptor and Michigan. Austin Blair was governor of Michigan from 1861 to 1865 and was a very strong supporter of the Civil War. He devoted great efforts to recruiting troops in Michigan. Census 1860 enumerated 110,000 men in military at ages of military service. Thanks, in part, to Governor Blair’s efforts, 90,000 Michigan men served or volunteered to serve in the Civil War. To honor his accomplishments, the legislature commissioned a statue of Governor Blair, the first to be erected on the campus of the capitol in Lansing. Edward Clark Potter was selected for that commission.

Sculptor: Edward C. Potter

Material: Polished gray granite from Concord, New Hampshire

Date of dedication: June 4, 1010; Dedicated by President William Howard Taft

State of Michigan Registry of Historic Sites: P3322, Listed June 15, 1992

National Register of Historic Places: Listed December 9, 1994

Photograph: Ren Farley; July 26, 2010

Description prepared: August, 2010

Return to Military Sites

Return to Public Art and Sculpture

Return to Home Page