By the late 1630s, the French explorers and missionaries had a reasonably accurate understanding of the geography of the Great Lakes and the major rivers that supplied those lakes with water. Indeed, by the 1630s, Etienne Brulé had sailed in all of the Great Lakes and found what would be recognized as the shortest route between the Great Lakes and the rivers feeding the Mississippi. Unfortunately, this was land route in northern Wisconsin from Lake Superior to the St. Croix River so it was not frequently used. By 1673, the explorer, Louis Joliet not only understood the location of the Great Lakes but comprehended the direction of the Mississippi River and knew that it flowed into the Gulf of Mexico, not into the Pacific Ocean. By 1682, René Robert Cavalier, Sieur de la Salle sailed the Great Lakes, followed a river route to the Mississippi and traveled north on the Mississippi and Illinois rivers to the Great Lakes. The French administration and missionaries had pretty completely and accurately mapped the geographic layout of the upper Midwest and the Mississippi valley by the late Seventeenth century.

Colonialism was not well understood in the early age of exploration. The French recognized that their rivals in Europe—Spain, Holland and England—were developing colonies in North America and recognized some possible strategic military value in possessing American colonies also. French colonies in the Caribbean were profitable because sugar and other commercial crops could be grown there, but the French colonies in present-day Canada were not agriculturally productive. Indeed, the French had to send foods to support settlers in this area. Furs were the most valuable product to be exported from the French North American colonies, but fur had to be obtained by trading European manufactured products to the Indians for their pelts. Transportation was a challenge since the Indians were few in number but spread across a vast area.

Mercantilist economic theories dominated French economic policy in the Seventeenth Century. The French understood that population was stagnant since high death rates offset birth rates. Population growth seemed unimaginable. Any loss of population in metropolitan France was seen as weakening the country in terms of its economy and its ability to amass personnel for wars against European enemies. So the French strictly controlled out-migration to their colonies. The British had more lenient policies. One of the major reasons why the English could expel the French from North American in 1760 was their demographic strength of the English colonies.

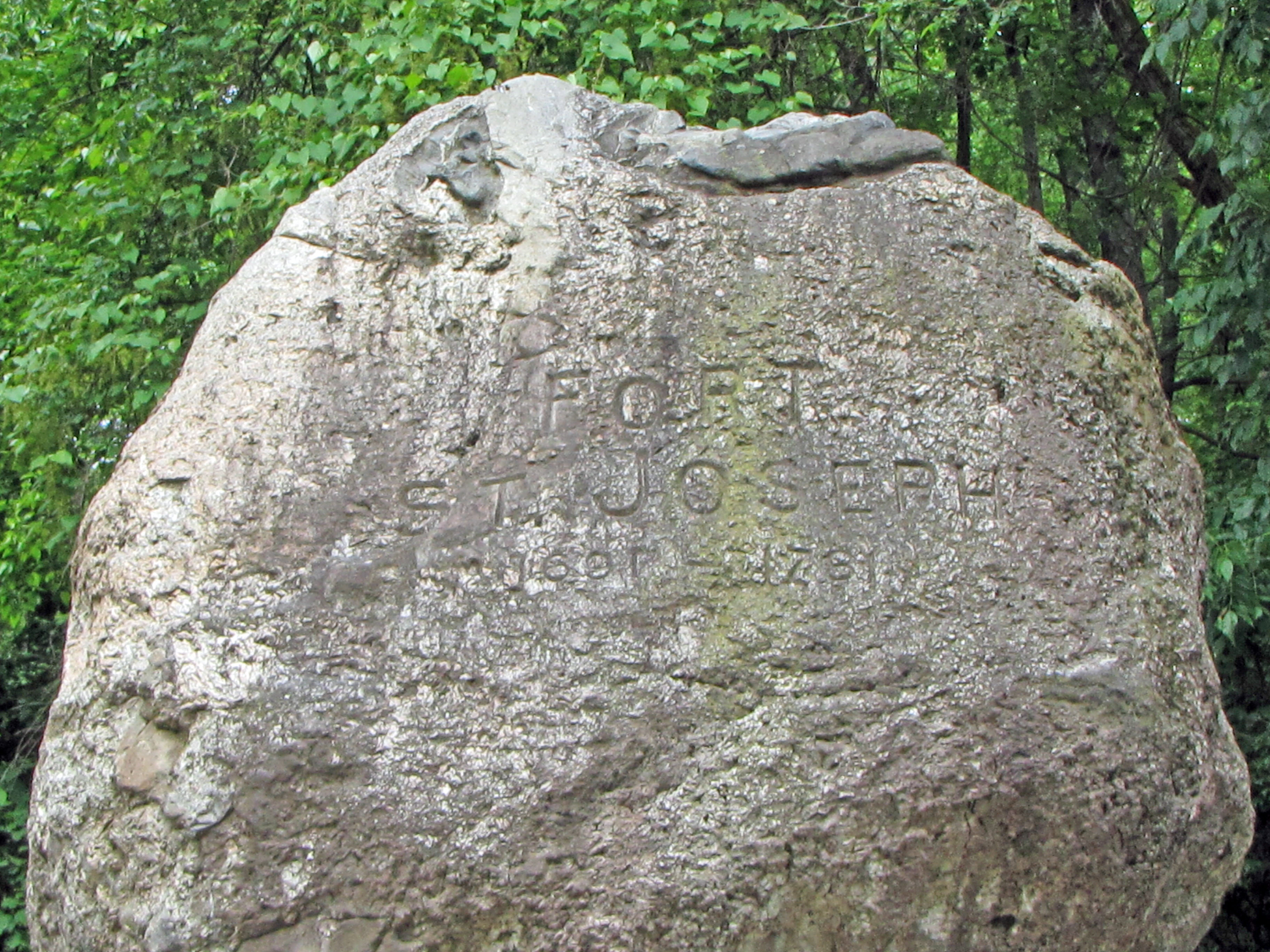

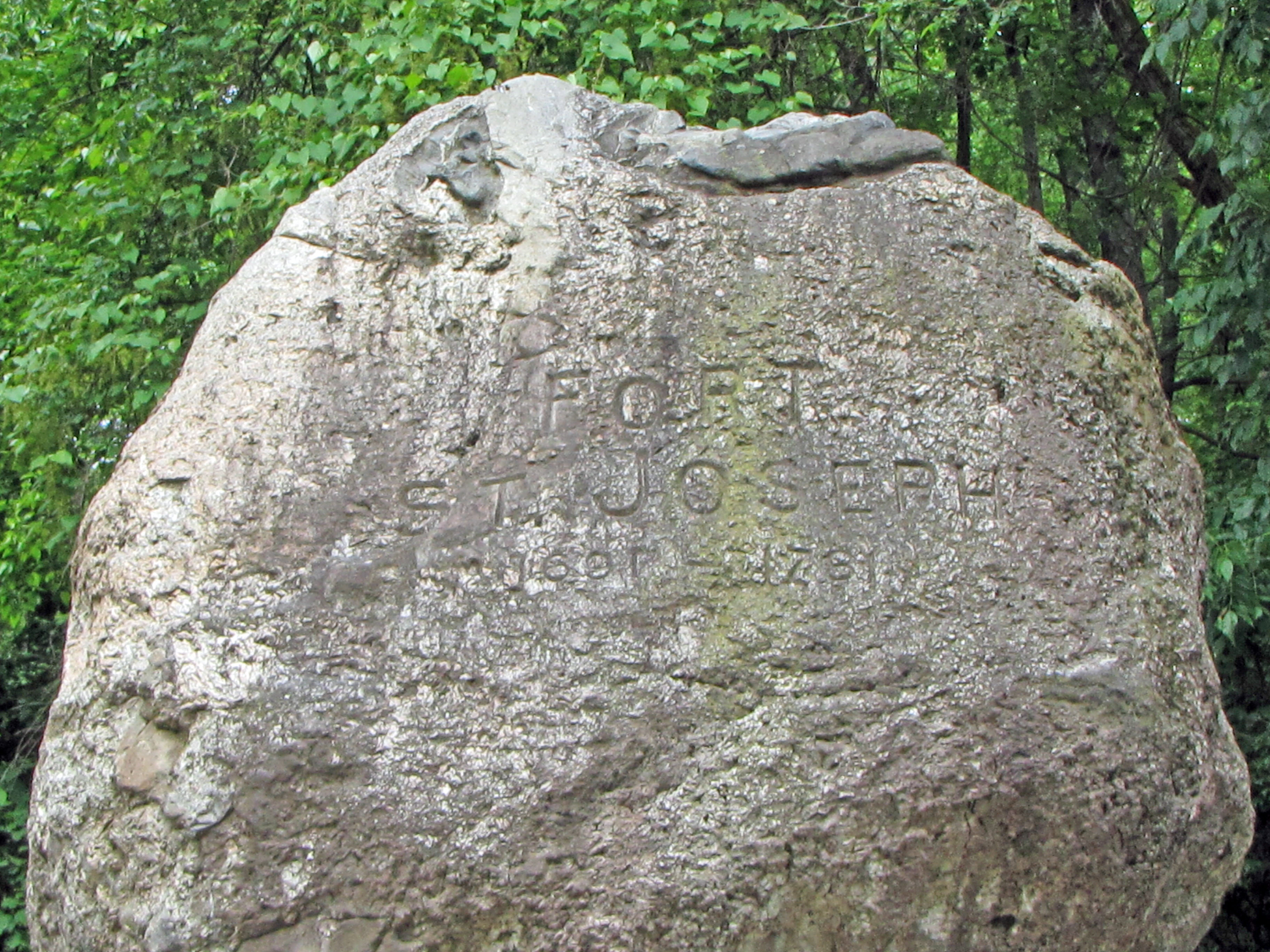

In 1680, French Jesuits obtained a land grant from the Crown to establish a mission on the St. Joseph River at the location we now know as Niles, Michigan. Pere Jean Claude Allouez founded a religious outpost there. Most all travel at that time was by water but Sauk Indians lived in Michigan. Unlike some other tribes, they established trails. Apparently, the Sauk had been pushed west from New York State by other tribes and by the time the French arrived in Michigan, they were once again being pushed west toward Illinois. One Sauk trail—later known as the Old Sauk Trail—extended from Detroit to the Mississippi River, passing close to present-day Niles and then Chicago. Another Sauk trail ran from North to South across Michigan and was later known as the Grand River Trail. The St. Joseph River ford for both of these trails was the location Pere Jean Claude Allouez selected for the Jesuit mission. Father Gabriel Richard, one of the key figures in Detroit’s history and founder of the University of Michigan, served one term in the early 1820s as Michigan’s representative in Congress. One of his major accomplishments was to secure federal funding to improve the Old Sauk Trail. About a century later, it was paved and is now know as US #12. It crosses the St. Joseph River about two miles south of the location of the 1680 Jesuit mission.

Illinois. One Sauk trail—later known as the Old Sauk Trail—extended from Detroit to the Mississippi River, passing close to present-day Niles and then Chicago. Another Sauk trail ran from North to South across Michigan and was later known as the Grand River Trail. The St. Joseph River ford for both of these trails was the location Pere Jean Claude Allouez selected for the Jesuit mission. Father Gabriel Richard, one of the key figures in Detroit’s history and founder of the University of Michigan, served one term in the early 1820s as Michigan’s representative in Congress. One of his major accomplishments was to secure federal funding to improve the Old Sauk Trail. About a century later, it was paved and is now know as US #12. It crosses the St. Joseph River about two miles south of the location of the 1680 Jesuit mission.

The French established numerous small military outposts—forts—along the frontier. These demonstrated French control of the territory and allowed the French to keep the Indians pacific. This they accomplished by providing generous gifts to Indian tribes every summer. French administrators could also try to control the fur trade. Late in the Seventeenth Century, it became apparent that some point toward the southern end of Lake Michigan would likely become a large trading center since it would be geographically linked to both the Atlantic trade through the Great Lakes and to the Gulf trade through the Mississippi River valley. In 1689, the French, led by Officer Augustine LeGardeur de Courtmanche began building a fort at this point. After that outpost was completed, it played the entrepôt role for this region, similar to the economic niche Chicago now fills.

These French forts were small and, while there may have been so settlers residing near them, they were few in number. These remote forts probably garrisoned one or two officers and a dozen or two enlisted men. Presumably, they could only be resupplied during the summer months when the lakes and rivers were navigable. Apparently it was not unusual for enlisted men to desert their post and run off to live with Indians where they acted as traders in the fur business. French administrators and the French clergy expressed tremendous contempt for French men who overthrew their Gallic culture and reverted to the ways of the Indians but it occurred frequently. The absence of French women and the willingness of many Indian women to cohabit or marry across the racial line, presumably, played a role in the emergence of a coureur de bois population. This was a pejorative term used to describe Frenchmen who became unlicensed fur traders. Those who held licenses were called by a much less derogatory term – voyageurs.

While France and England were fighting the Seven Years War in Europe, the mirror image of that war in the American colonies was known as the French and Indian War. After losing major battles to British and American forces at Quebec City and Montreal in 1759 and 1760—and losing many other skirmishes—the French quickly surrendered their Midwestern forts to the English, including this one and the one at Detroit. The British dispatched minimum numbers of personnel to occupy these isolated forts, although they wished to clearly establish their control of the area west of the Alleghenies. Many Indians saw the British as adopting extremely harsh policies. For example, the British viewed the generous gifts the French gave the Indians every year as nothing other than bribes and ceased the practice. This may help to explain why Chief Pontiac from 1761 through 1763 organized Indian tribes to effectively rise up against the British, Presumably their aim was to expel British settlers from west of the Alleghenies. Their expectation that the French would send troops to assist them in their battle against the British was not fulfilled. The Indians were successful in capturing all of the British forts in the present day Midwest except for those at Detroit and Pittsburgh. Potawatomi attacked Fort St. Joseph at Niles and apparently killed all the British soldiers stationed there except for the commander, Ensign Francis Scholser. He was kept alive and taken to Detroit where the Indians exchanged him for ransom. Chief Pontiac’s rebellion petered out in the summer of 1863 and the British reoccupied Fort St. Joseph.

Niles, Michigan claims to be the City of Four Flags. The city’s promoters point out that it is the only location in Michigan that was occupied by four powers: France, England, Spain and the United States. Their claim is accurate but the Spain came and left in the twinkling of an eye.

De la Salle claimed the Louisiana Territory for France in the 1680s. No European nation disputed that claim. Spain cast their lot with the French in the Seven Years War in Europe. That conflict ended with the Treaty of Paris in 1763 and the French gave up almost all of their empire in North America. Leading up to the Parisian negotiations, King Louis XV of France secretly transferred ownership of the Louisiana Territory to King Charles III of Spain. He did not announce that transfer for about two year. King Charles III was the cousin of King Louis XV.

Few people, if any, appreciated the value of the Louisiana Territory which extended from the mouth of the Mississippi to the headwaters of the Missouri in Montana. After 1763, the French population of the Canadian Maritimes was expelled by the British. Many came to Louisiana where they became the forebears of the Cajun population that continues to speak French and plays an important demographic role in Louisiana.

By 1770, the Spanish crown began sending administrators to the Louisiana territory. The one outpost of any size, other than New Orleans, was St. Louis. During the American Revolutionary War, the Spanish sided with the English but were not very actively involved. Most of the Revolutionary War was fought along the East Coast, but from time to time, those supporting American independence attracted British forts in the remote Midwest. A group of American revolutionaries led by Jean-Baptiste Hamelin and Lieutenant Thomas Brady came from Cahokia, Illinois and attacked Fort St. Joseph in 1780 but were repulsed. After that episode, two Milwaukee chiefs, Naquiguen and El Hetturnó, approached the Spanish commander in St. Louis, Don Fransco Cruzat, and claimed that they could accomplish what the Americans had failed to do. They were willing to raise a troop of Potawammie warriors who would capture Fort St. Joseph, but their price was half of what was taken from the military outpost. Cruzut agreed to the deal and dispatched Captain Don Eugenio Pouré to lead a force composed primarily of Indians. They stormed the fort on the banks of the St. Joseph River on February 12, 1781, drove off the small British force and raised the Spanish flag. They spent the next day plundering the fort, then took down the Spanish flag and arrived back in St. Louis on March 6, 1781. The time the Spanish flag flew over Michigan should be counted in hours and minutes, not months and years.

Even though the American colonies won their independence, the British continue to occupy their forts in Detroit and Niles. Until President Washington sent troops to defeat the Midwestern Indians who were then friendly with the British, the English maintained their control. Finally, the United States and England signed Jay’s Treaty in 1795 and the British withdrew their forces from Niles, St. Ignace and Detroit.

After American independence, the Spanish pressed their claim to control of both Florida and the Louisiana Territory. Most disturbing to the new nation was the refusal of the Spanish to allow Americans to ship any products through New Orleans. The United States and Spain negotiated these matters and signed the Treaty of San Lorenzo in 1795. The major provisions allowed Americans to use the Mississippi River and establish the northern border between the United States and the Spanish colony of Florida. However, in these treaty negotiations the Spanish unsuccessfully pushed a claim for Michigan based on the one day in February, 1781 when Indian forces led by Spanish captain Don Eugenio Pouré controlled Fort St. Joseph.

I do not believe that the American military occupied Fort St. Joseph after the British departed in the late 1790s. The first settlers came to Niles in the 1820s, a population migration that increased after 1848 when the Michigan Central Railroad reached the city. An historical marker was placed as a presumed location of this fort in 1957. However, the precise location of the fort was not unambiguously established until archeologists and archeology students from Western Michigan discovered French detritus in 1998.

Date of first settlement: 1680

Date of construction of first fort: 1688 to 1691

Use in 2010: Historical Site

Website of the Museum of Fort Joseph: http://www.ci.niles.mi.us/Community/FortStJosephMuseum/OverviewFortStJosephMuseum.htm

State of Michigan Registry of Historic Sites: P22614, Listed February 18, 1956

State of Michigan Historical Marker: Put in place: April 19, 1957

National Register of Historic Places: Listed May 24, 1973

Pictures: Ren Farley; June 4, 2010

Description prepared: June, 2010

Return to Military Sites

Return to Home Page